So, being as it’s getting time for me to be writing about some of my writing systems, I got to realizing I didn’t really have a good idea how to describe writing systems. For a grammar it’s relatively easy—just pull out a copy of Describing Morphosyntax and go at it—but for conscripts (and natscripts) I’m not aware of such a guide. So of course I decided to put one together.  Now, I know this looks like a questionnaire, but your results probably won’t read well if you just sit down and answer each question one by one; your best bet is to use this as a starter for things to write, and you’ll know you’re done if you’ve written something that answers most of these questions.

History and Origins

Describe the script’s origin. Who are recognized as being first to use it, where, and when? Can it be shown to evolve gradually from an earlier script, or is its earliest appearance an abrupt change from its parent? Is its creation attributed to an individual person historically or in legend? If so, tell this story. What is the oldest surviving example of text in this script?

Antecedent scripts

Show a table (comprehensive, preferably) comparing letterforms in the script with the parent script’s forms. Are there any particular factors involved in the changes between the new forms and the old, for example a change in writing materials? Are there letters in the script that don’t correspond to anything in the parent? If so, where do they come from? Compare this script to others with the same ancestor.

Descendant scripts

Are there any scripts that descend from this one? If so, what circumstances caused the split? Are there letters in the script that don’t correspond to anything in the daughter script? If so, where did they go? Did this script fall out of use when the daughter script began to be used, or is it still used for other purposes?

Discovery

If the script was “lost” at any time, describe its rediscovery. Who discovered it, and where? Was it recognized immediately for what it was or was it misidentified as a similar script? Was it undecipherable?

Palaeography, epigraphy, archaeology

Where are ancient examples of this writing found? Are there any well-known or notable script-bearing artifacts? Describe any famous fakes.

Decipherment

If understanding of the script was ever lost, has it since been redeciphered? By whom? Tell this story. How long did it go undeciphered? Describe well-known failed decipherment attempts.

Description and structure

What kind of script is it—an alphabet, an abjad, an abugida, a syllabary, a mixed system, an arrangement of tentacles or musical notes? In what direction is it written? Relevant details to the type of script—If it’s an abjad, is there a way of representing vowels when necessary, and when is it customary for it to be done? If it’s an abugida, what’s the inherent vowel? If it’s a syllabary, how are coda consonants or consonant clusters handled? If it’s a more outlandish system, describe how it works.

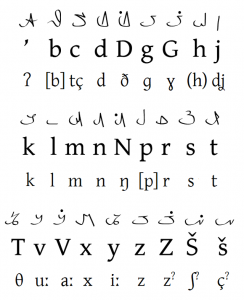

Grapheme inventory

Include a chart of the basic characters in the script as they appear in ordinary type—individually, if possible, or with a basic combining character if not. Include their most common or most representative phonetic values. Do the characters have names outside of the sounds they represent? If so, what are they and where do they come from? Are any of the characters obsolete? Is there controversy over whether certain characters are fully nativized members of the script or just foreign borrowings? Is there an upper and a lower case?

Writing the letters

Include a chart of the basic characters in their handwritten form, and show how to write them. Is there a “correct” system to writing letters, or do people have relative freedom in writing? Indicate any characters that differ substantially in handwritten form from printed form. If there are multiple writing styles, such as block letters vs. cursive, describe them and their differences. When is one variant used over another? Are specific writing implements preferred for one variant or another? What order are they taught in? Go over the calligraphic tradition.

Transliteration and transcription

Describe any standard transliterations of the language into Latin letters and/or other scripts in the area it is used. Are any letters considered as being “the same” as letters in similar scripts? How are sounds foreign to the script typically handled? (Letter borrowing, nearest approximate sound, writing words wholesale in the original script, or…?) If strict transliterations tend to have outlandish results, are there any standard transcriptions used instead?

Ligatures and conjuncts

List any common or necessary ligatures or conjoinments of letters. Do any languages using the script treat any of these ligatures as individual letters? Are ligatures part of everyday writing, or do they indicate fine or formal typography? Are there circumstances (e.g. based on phonetics) where ligatures are not to be used?

Diacritics and letter modifications

List any diacritics in use. What are the origin of the diacritics? Do they have a unified meaning (e.g. ‘acute means palatalization’) or do they tend to have a more or less ad hoc relationship to the letters they are used on? When, if ever, is it acceptable to omit diacritics?

Punctuation and symbols

List common punctuation. Are words separated by a space, by a visible interpunct character, or not at all? Describe what, if any, punctuation is used: between sentences, paragraphs, and various clauses; to break words at the ends of lines; to introduce and delimit quotations; to indicate proper names; to indicate pauses, questions, exclamations, sarcasm, omissions, trailing off… Describe any other symbols in common use.

Numerals

List the numerals in use. What base are numerals written in? Is the base for the numeral system the same as the base for number words in the languages using the script—and if not, how did this difference come about? What is the origin of the numbers—are they borrowed, do they derive from the native graphemes, are they originally tally marks? Are large numbers separated at convenient intervals? What symbol is used as the decimal point?

Collation

What order are the graphemes generally given in? Do any of the graphemes count as a different underlying value when sorted? Do any languages using the script have a substantially different sort order?

Sample of the script in use

Give an example text using the script, with a transliteration.

Usage, applications, literacy

Who uses the script? Is it in everyday use, or is it only found in restricted contexts, such as in religious settings or on monuments? How high is literacy among users of languages the script is used to write? Is it used by everyone, or chiefly particular groups of people? Compare the script to others used in similar contexts.

Variants, reforms, standardization

Does the grapheme inventory vary from place to place or over time, even within the same language? Have there been any major changes to the script instituted by governments or notable individuals? Is the script relatively standard, or is the “standard version” a generalization from various regional variants? Describe any major political or regional variants of the script.

Languages written with

List all languages the script is used to write, and when and where it is so used.

Adaptations for various languages

Describe any major language-based variants of the script. List any additional letters, diacritics, or symbols along with which language uses them, and what they are for.

Typography

Describe the language’s typographical history. What was the first work printed in this script? Who designed the original typefaces? Describe the major typographic styles (e.g. roman, italic, serif, sans-serif). Describe any unusual features of typeset text (e.g. lettershapes that differ significantly from their written forms).

Computing

Do contemporary computers handle correct display of text in this script? If not, how is support broken? (e.g. no character encoding, no ligation, no complete fonts, no support for the correct text direction) How is/was the script handled with computers not treating this script correctly—transliteration? Kludges? What was the first program or operating system to implement it correctly?

Keyboard layouts

Give a diagram of the usual keyboard layout(s) for this script. Who invented the layout? Is it original or based on that of another script? Can inputting the script be done directly from individual keys on the keyboard, or are there dead keys or IMEs to facilitate input of more complex features?

Unicode and other technical standards

If the script is in Unicode, give the chart of the Unicode block(s) where the script is encoded. When was it included in Unicode? Were there any controversies regarding encoding it in Unicode? Are there any errors in Unicode’s description of the characters? List any other character encodings designed for or including this script. Are they still in use?

Most of these headings I got from Wikipedia articles. Â If you just happen to be writing that sort of thing, you’ll also want to include sections like “References” for footnotes, “Bibliography” or “Further Reading” for book sources, “See also” for related wiki pages on the same site, and “External links” for the obvious.

Tagged description, grammatology, scripts